D. Michael Lindsay

Reviewed by: D. G. Hart

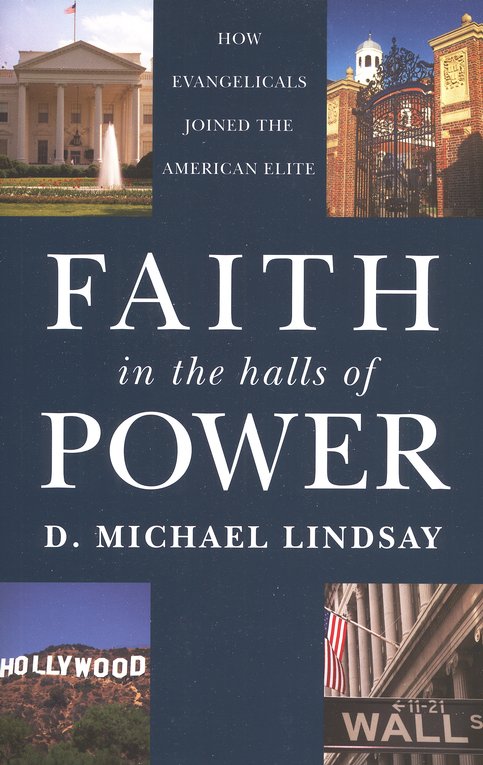

Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite, by D. Michael Lindsay. Published by Oxford University Press, 2007. Hardback, 349 pages, list price $24.95 (paperback, $16.95). Reviewed by historian and OP elder D. G. Hart.

What counts for success in the Christian world? Some look for material evidence: the number of people who attend church, the number of books sold, the amount of money given to a religious organization, or the size of a beautiful new building. Others look for spiritual evidence, such as personal growth in grace, maturity within a congregation, or greater theological discernment among a communion's pastors and elders.

D. Michael Lindsay, a sociologist at Rice University and the author of Faith in the Halls of Power, does not take a side in this debate, but assumes, as his subtitle indicates, that joining the American elite is an accomplishment indicative of success. In fact, he is so indifferent to the difference between material and spiritual evaluations that he seems to be unaware of the ambiguity of his title. His book is about evangelical Protestants who have become leaders in various sectors of American society.

Evangelical Protestants emerged in the 1940s with the goal to "interject moral convictions into American public life." Lindsay does not question this outlook and comes close to celebrating it through a method called "critical empathy," which tries to describe as accurately as possible the ideas, aspirations, and intentions of subjects. As a result, this book not only describes evangelicals "in the halls of power," but also evangelicals' faith in using the halls of power to accomplish God's purposes.

Lindsay does a better job of describing what evangelicals think they are doing than persuading readers that born-again Protestants have actually joined the American elite. He interviewed 157 evangelical leaders active in government, education, the arts, and business, and assessed the strength of evangelicalism on the basis of these interviews. The subjects range from James A. Baker III to Jimmy Carter, Tony Dungee to Os Guinness, Tim Keller to Mark Noll.

Yet the responses and Lindsay's analysis do not demonstrate evangelical power. To be sure, the landscape of evangelicalism is much different today than it was when Billy Graham was starting his career as an evangelist in the 1940s. Then the nomination of a Pentecostal for Vice President (Sarah Palin) or a Southern Baptist (Rick Warren) interviewing the presidential nominees during prime time was unimaginable. At the same time, the hostility that Warren and Palin have experienced suggests that evangelicals are still outsiders in a culture dominated by major newspaper editors, faculty at Ivy League universities, and businessmen like Bill Gates and George Soros.

Lindsay may be too close to his subject. He often sounds more like a publicist than a sociologist. A related and deeper problem is that he never seems to have considered these words of the Christ whom his powerful evangelicals say they serve: "What does it profit a man to gain the whole world, and forfeit his soul?" That may seem like a heavy-handed way of evaluating a believer's success. But it is a reminder that Christians have a more exacting standard for assessing influence than the methods of secular sociology.

March 30, 2025

On the Trail with a Missionary

March 23, 2025

Midnight Mercies: Walking with God Through Depression in Motherhood

March 16, 2025

March 09, 2025

Zwingli the Pastor: A Life in Conflict

March 02, 2025

February 23, 2025

African Heroes: Discovering Our Christian Heritage

February 16, 2025

© 2025 The Orthodox Presbyterian Church